The Stasi’s forgotten victims struggle to celebrate thirty years of German reunification

3 October 2020

Thousands of former GDR citizens could still be living with trauma from the Stasi's political persecution. But victims say their story was sidelined after reunification.

The city of Leipzig's St. Nicholas Church, became the centre of a peaceful revolt against communist rule, which led to the fall of the Berlin Wall.1

For Maria K., the fall of the Berlin Wall was one of the most incredible moments of her life. “It was like witnessing one of the world’s seven wonders,” she said.

But as Germans mark the thirtieth anniversary of the country’s reunification, Maria has unresolved grievances. “I have nothing to celebrate,” she said, “I had imagined a different Germany.”

Maria, now in her 70s, fled the Soviet-backed German Democratic Republic in June 1989, and was living in a refugee camp in West Germany. “Four weeks before the wall came down in November, Erich Honecker, the ruling party’s General Secretary, said the wall would remain in place for another 100 years,” she recalled.

She is among the thousands of Germans who fled political persecution from the GDR. “I fought for change, and I was deemed a traitor and an enemy of the state,” she recalled.

Traumatic memories of this persecution still haunt Maria to this day. “With the pandemic I’ve spent a lot of time alone, and I had more time to reflect on the past,” she said.

She spoke to me via a video-call, from the only centre in Germany that provides therapy for victims of the GDR’s political persecution. Both she and the centre’s staff requested anonymity due to the sensitive nature of the subject.

This week, German President Frank-Walter Steinmeier awarded the sociologist Kathrin Mahler Walther a Federal Cross for her youth activism in the former GDR.

But Maria’s story, as well as other victims of the GDR’s state authorities, is seldom acknowledged in public celebrations for German Unity Day. “Our group is forgotten by society,” she said.

Our church group events typically attracted 600 to 1000 people. About half of those were informants.

The GDR's Ministry for State Security, better known as the Stasi, was notorious for its surveillance operations which cracked down on dissenters. Suspected dissidents faced arbitrary arrests, intimidation and were often ostracised by their friends and relatives.

“They were threatened and intimidated. They were denied jobs and promotions. They lived with a constant sense of failure and helplessness,” said a psychologist working with trauma victims at the centre. Family members were also spied on or punished.“Sometimes they didn’t know why this was happening to them,” said the psychologist.

The Stasi’s methods are often mischaracterised as “non-violent” because of their psychological nature. The last documented instance of physical torture in the GDR, some historians say, was in 1951.

“It was the special consequence of a divided Germany. The state authorities could not behave like the KGB, because they were so close to the West,” said Tobias Wunschik, a researcher at the Stasi Records Agency, a state archive for Stasi documents.

One of their key interrogation methods produced a form of dissociation. “They could spread bad rumours about a person among their family, to the point that the person became disoriented. There was a disintegration of the self,” said Wunschik.

Decades later, the damage inflicted on victims still lingers. “Victims suffer from trust issues, they struggle to find jobs and to maintain working relationships,” added the psychologist.

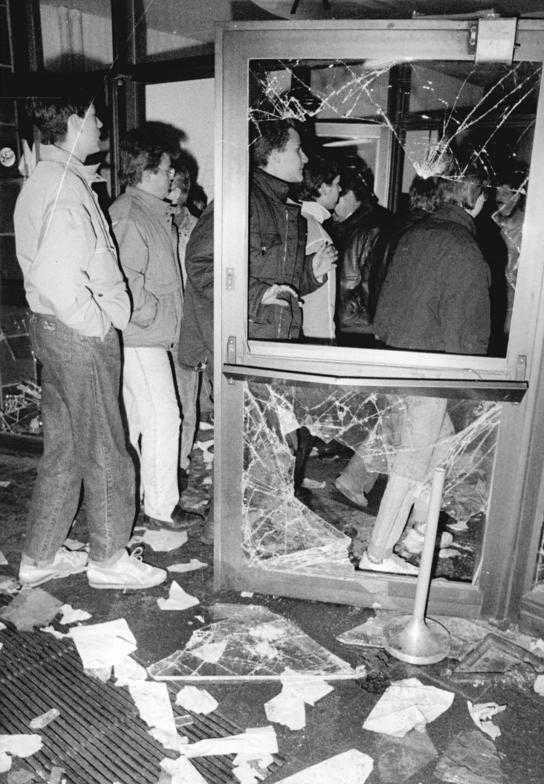

Protestors storm the Stasi headquarters in Berlin, 15 January 1990.2

Protestors storm the Stasi headquarters in Berlin, 15 January 1990.2

Maria was targeted by state authorities for her activism with a Protestant church group, which promoted freedom of speech and documented human rights violations. She was married then, and worked as a costume designer at the Komische Oper, an opera group in East Berlin.

“One morning, they arrested 11 members of our group. I was barred from my job, and demoted to the cloakroom and cleaning toilets,” she said, “My salary was cut from 800 to 300 marks.” Her applications to leave the country were rejected three times, until finally, in June 1989, she fled to West Germany.

As part of its extensive surveillance operations, the Stasi operated a network of hundreds of thousands of informal informants. “Our church group events typically attracted 600 to 1000 people. About half of those were informants,” said Maria.

Over decades millions of reports about the country’s citizens were amassed in the Ministry’s headquarters. A law passed in 1991 gave every individual the right to view the Stasi’s records about themselves.

Today, the Stasi Records Agency receives about 30,000 requests for personal files viewings a month.

When Maria accessed her own file in 2004, she discovered that one of the informants had been her husband. “We were separated by then and I wrote to him. In response, he accused me of defamation and threatened me with a lawsuit,” she said.

“That’s when I sought help and started coming to the centre,” she said.

I fought for a change that would have people of all classes fairly treated and represented. I had imagined a reunited Germany to be more neutral.

Today, the victims’ trauma is often tied to the ensuing economic fallout that affected those states after reunification. Maria, like many former citizens of the GDR, receives a much smaller pension than her West German contemporaries.

“I fought for a change that would have people of all classes fairly treated and represented. Capitalist life is difficult, even after thirty years,” said Maria.

Likewise, the current political climate in Germany has led victims like Maria to question the process of reunification itself. “I had imagined a reunited Germany to be more neutral. Instead, the far-right is on the rise, and the political party Alternative für Deutschland is gaining more power. Extreme leftist movements are emerging in response,” she said.

Artworks from the centre’s art therapy sessions testify to these social and political upheavals.

In one of Maria's drawings at the centre, a woman stands between four buildings: a church, a housing block, a German car manufacturer, and a home with grass and flowers. On top of the housing block, she has drawn a French flag and a mosque with a flock of birds.

The names of German supermarkets appear in the center, and beneath it, a reference to the current German Chancellor Angela Merkel. For former citizens of the GDR, the leader is better known as the daughter of a pastor who also grew up in the former republic.

German Unity Day celebrations outside the Reichstad, Berlin, 3 October 1990.3

German Unity Day celebrations outside the Reichstad, Berlin, 3 October 1990.3

Thousands of former GDR citizens could still be living with trauma and without proper support. “Often clients were not aware that the centre existed, or that their feelings and behaviour were connected to trauma,” said the psychologist.

Yet the issue seldom forms part of public debate, and critics say it has been deliberately overlooked by the positive narrative of reunification.

This is felt on German Unity Day, where victims of the GDR’s political persecution feel sidelined. “Feeling voiceless is a symptom of trauma, but when this trauma itself is ignored in public debate, it exacerbates the feelings of voicelessness,” said the psychologist.

Maria hoped that victims of political persecution would finally be recognised. “I am just a small, small victim. Many were imprisoned,” she said, "I want their stories to be heard, so that they find their place in history.”

Originaltransparente der Friedlichen Revolution. (Photo: Bernd Schmidt / Creative Commons)

Protestors storm the Stasi headquarters in Berlin, 15 January 1990. (Photo: Peter Zimmermann / German Federal Archives) Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-1990-0115-034 / CC-BY-SA 3.0

German Unity Day celebrations outside the Reichstad, Berlin, 3 October 1990. (Photo: Thomas Uhlemann / German Federal Archives) Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-1990-1003-417 / CC-BY-SA 3.0